Trainspotting

Everyone is talking about it: Director Danny Boyle at Telluride Film Festival, where he showcased hotly anticipated biopic Steve Jobs, announced his next film would be Trainspotting 2. Written by the BAFTA winning John Hodge, and based on Irvine Welsh’s Porno (the novel sequel), the movie is set to bring back all the original cast including Ewan McGregor and Johnny Lee Miller. It’s a tentative announcement. Nearly twenty years after the original first came to prominence, the now cult fan favourite is still on that scummy pedestal, steaming with decay and delicate visceral emotion. A new addition to that masterpiece of human degradation may have missed the shit-stained boat, begging the question; “can’t we leave films alone?”

Everyone is talking about it: Director Danny Boyle at Telluride Film Festival, where he showcased hotly anticipated biopic Steve Jobs, announced his next film would be Trainspotting 2. Written by the BAFTA winning John Hodge, and based on Irvine Welsh’s Porno (the novel sequel), the movie is set to bring back all the original cast including Ewan McGregor and Johnny Lee Miller. It’s a tentative announcement. Nearly twenty years after the original first came to prominence, the now cult fan favourite is still on that scummy pedestal, steaming with decay and delicate visceral emotion. A new addition to that masterpiece of human degradation may have missed the shit-stained boat, begging the question; “can’t we leave films alone?”

Anyway, between terror and excitement, lies the Trainspotting news and thousands of fans probably, like me, piled back into the worst toilet in Scotland to revel in the goodness that was Danny Boyle’s 1996 classic (which now celebrates it's 20th Anniversary). So why did the original work so well?

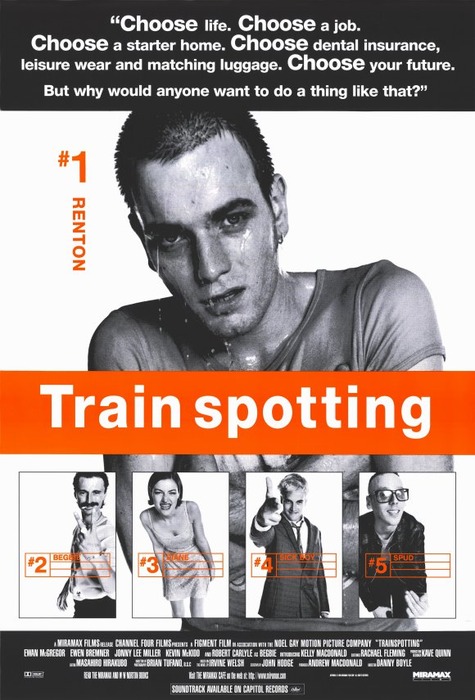

Trainspotting, for those who don’t know, follows the life of Renton - a twenty something heroin addict who has no prospects or ambitions, living in the poor landscapes of Edinburgh and all its ruins. Surrounding him are mates in equal states of despair, and it movie follows them in all their debauchery to either get clean or get their next fix…

Propelling Ewan McGregor into stardom, this is very much the actors feverish, raw, and cheeky best - wrapped around a toilet pan and sunk into a carpet. Mark Renton, our narrator who takes us down the streets of Edinburgh, is young and, despite his drug use, is enthused with blind hope leading to blind desperation. McGregor is entertaining and charming in this ultimate state of despair where life is the disease and drugs are the cure. Around him, the likes of Lee Miller, Robert Carlyle, Ewen Bremner, and Kelly MacDonald all fashion a fulfilling cast of characters that decorate Renton’s life with love, anger, rage, and selfishness all at once.

Hallucinogenic and depraved, Boyle’s work holds back nothing when underscoring just how wretched the life of an addict is. Visually haunting, the redolent, ravenous, and repulsive setting of Renton’s rehabilitation and debilitation cycle is painted with vile aesthetics and nightmarish vision that never allow the audience to de-grip from their armchairs. With the film burnt truly into the skull of every viewer, Boyle shocks but ultimately delivers an achingly beautiful side of addiction that, whilst not glamorised, showcases the intricate connections and beating truth beneath the decent of drug infused fog our characters relish in.

This is where Trainspotting propels from an unnecessary movie about drug use and into an important sickly stylish film about human desperation. See, the film provides no real reason or rhyme for why the rambunctious group would dally in heroin, nor does it need to. Frankly, boredom and self-destitution is enough to force them into injecting brown liquid into your veins. But Boyle, Hodge’s script, and Welsh’s original novel all flicker this pulse of misery to feel close and connected to those around you and, in many ways, yourself.

And if you think that’s, in some way, overreaching because Trainspotting doesn’t present characters with any type of moral compass as it spirals down the toilet - then accept the fact that, sometimes, films don’t have to. Humanity can be dark and desolate without having the fuzzy warmth of goodness. But Trainspotting dredges the barrel of humanity, finds these heroin addicts, and fills them with emotions and feelings. However wrong the characters feel here, the creative minds behind the film showcase something that many find hard to face: They are still humans with thought processes and emotions, all deserving of some sort of chance and choice…

Help them choose life.